Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis

Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has become the leading chronic liver disease in the developed world, with a prevalence of 6%-35%. Its pathological spectrum ranges from simple steatosis (non-alcoholic fatty liver) to different degrees of inflammation and liver cell damage [non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)]. NASH has gained attention in recent years because of its association with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although the occurrence of HCC is more frequent in the presence of cirrhosis, studies have shown that hepatic carcinogenesis may also develop in the context of NASH without association with advanced fibrosis, as well as from simple steatosis. Evidence of the onset of HCC in the absence of cirrhosis is of concern, since recent surveillance and screening guidelines for liver cancer do not include this population subgroup. Therefore, it is imperative that new effective screening and monitoring measures for HCC, or even the reformulation of these recommendations, be taken to handle these patients considered to be at high risk. The present paper aims to review the literature on the occurrence of HCC in patients with NASH with or without cirrhosis. In addition, we report a case showing the development of HCC in a patients with NASH without cirrhosis.

Keywords

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the leading cause of liver disease in the world and its pathological spectrum ranges from simple steatosis [non-alcoholic fatty live (NAFL)] to various degrees of inflammation and liver cell damage, a condition known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[1-4]. The diagnosis of NAFLD requires the exclusion of excessive alcohol consumption, defined separately for men and women, and other secondary causes of liver disease. For definitive diagnosis of NASH, currently, a liver biopsy is needed[4].

A hypercaloric diet with excess saturated fats, refined carbohydrates and high fructose consumption has been related to weight gain and, more recently, to NAFLD[4,5]. Thus, NAFLD is associated with metabolic syndrome and is characterized by adipose tissue dysfunction and insulin resistance. These two factors generate deregulation in the production of adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory protein, and increase the release of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, leptin and interleukin-6. The effects of this imbalance lead to the deposition of lipids in hepatocytes, causing lipotoxicity and the production of free radicals by the oxidation of fatty acids. The progression to NASH occurs in 25 percent of cases[1]. Also, gut microbiota plays a role in inflammation, through alterations in gut epithelial permeability, choline metabolism, endogenous alcohol production, release of inflammatory cytokines, regulation of hepatic toll-like receptor, and bile acid metabolism[6].

Estimates of NAFLD prevalence range from 25%-45% in the US, while NASH currently affects 5 percent of the population[7]. As diabetes and obesity have become global epidemics, the WHO predicts an exponential increase in cases of NAFLD in the coming decades[2]. The objective of this study is to review the literature on the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the context of NAFL/NASH with or without associated cirrhosis.

Case report

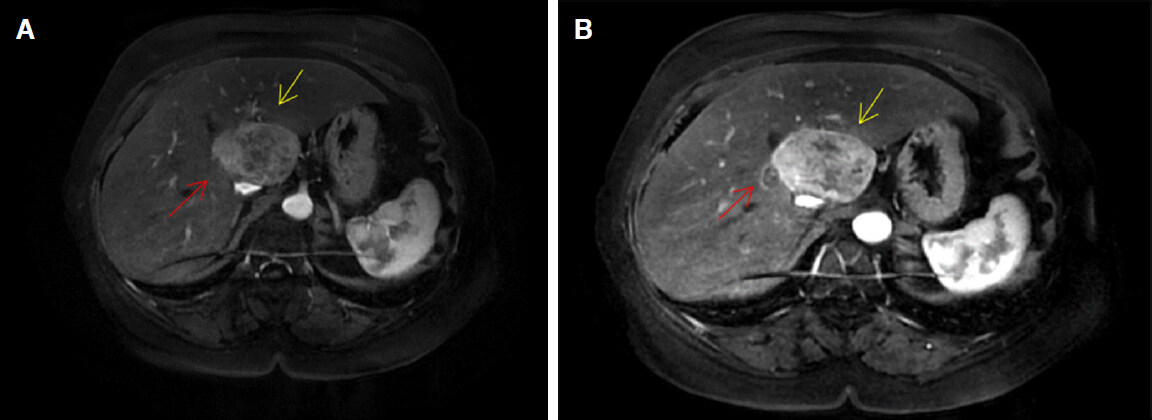

A 67-year-old female patient, from Caxias do Sul, sought care due to a complaint of asthenia, inappetence and a weight loss of 3 kg over the last month. The patient displayed metabolic syndrome, with a previous diagnosis of grade I hepatic steatosis, diabetes mellitus type 2, mild obesity and arterial hypertension. The patient was admitted in the hospital for investigation of hepatic nodules identified in an ultrasonography. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a heterogeneous nodule, in hepatic segment I, measuring 5.7 cm (largest measurement) and another nodular image in segment II measuring 1.9 cm (largest measurement), with homogeneous arterial impregnation (suspected for HCC - Figure 1). A biopsy of both nodules and of the liver was performed, guided by ultrasonography.

Figure 1. Hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrated in magnetic resonance of the abdomen. Yellow arrow - larger nodule (5.7 cm); red arrow - smaller nodule (1.9 cm)

The patient remained in good general condition throughout the hospital stay. Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, hematocrit 32.9%, prothrombin time 11.1 s, total bilirubin 0.2 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 113 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 25 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 28 U/L, gama glutil transferase 73 U/L, albumin 5.01 g/dL and alpha-fetoprotein of 6.7 ng/mL were performed. The biopsy revealed that liver presented: nodulo I with macrovacuolar steatosis in 10 percent of hepatocytes, portal lymphocytic infiltrate, no fibrosis and hepatocellular ballooning and nodule II with hepatic lesion with desmoplastic stroma and small cells with mild nuclear pleomorphism, an image corresponding to HCC.

The patient was diagnosed with NASH associated to HCC. After histological confirmation, she was referred to the clinical and surgical oncology service for tumor resection.

Discussion

NASH has gained attention in recent years because of its association with HCC[1,3]. It is known that there is a risk of progression to advanced fibrosis in up to 20 percent of patients with this pathology, thus increasing the chance of developing liver cancer[1,8-11]. Studies have found that 11.3% of patients with cirrhosis due to NASH developed HCC within 5 years, while in patients with cirrhosis due to alcohol, the rate is 12.5% over the same time frame[1]. Compared with the benign course of NAFL, NASH patients have an 8-fold increased chance of progressing to advanced fibrosis, in addition to an increased risk of liver-related death and of cardiovascular disease[2,12]. The main risk factors involved in the occurrence of HCC in cirrhotic patients due to NASH are male gender, age over 70 years-old, diabetes and hypertension[13]. It was estimated that the presence of NAFLD-associated HCC is 7.6-fold greater than in a same sex and age control group[14]. Nevertheless, the impact of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in HCC is still greater than that of NAFLD - the risk for HCC in cirrhotic patients with HCV is three times greater than that of patients with NAFLD[15]. Considering only studies strictly including patients with or without cirrhosis, the reported incidence of HCC in NAFLD patients with cirrhosis was between 6.7% and 15% at 5-10 years, whereas the incidence in NAFLD patients without cirrhosis was 2.7% at 10 years and 23 per 100,000 person-years[16].

The prevalence of NAFLD has become similar in the West and the East[17]. Obesity, which has been mostly a health problem of the Western world, has emerged rapidly in Asia, due to globalization and rapid urbanization, which lead to a change of dietary patterns to those of the West[18]. In China, the number of obese people has increased from below 0.1 million in 1975 to over 43.2 million in 2014, accounting for 16.3% of obese people worldwide. In India, the number of obese people increased from 0.4 million to 9.8 million during the same period[19]. This will increase the prevalence of NAFLD in Asia, which will in turn increase the cases of HCC not only from the increasing prevalence of NAFLD but also from the anticipated decreasing burden of HBV and HCV infections. It is a fact that primary, secondary and tertiary preventive strategies for HCC due to NAFLD are lacking. NAFLD has been estimated to contribute to 10%-12% of HCC cases in Western populations and 1%-6% of HCC cases in Asian populations. The increasing burden of NAFLD-related HCC over time has been demonstrated in studies from both Western and Asian populations[20]. For example, in a Sri Lanka cohort, the most common cause of HCC was NAFLD-related cirrhosis[21]. Hence the global incidence of NAFDL is increasing rapidly, its impact on HCC incidence may be explosive[22,23].

Although HCC is more frequent in the presence of cirrhosis, several studies have shown that hepatic carcinogenesis may also develop in the context of NASH or NAFL, without association with advanced fibrosis[1-3,7,24]. A 2.5-fold increased risk of developing HCC in patients with NAFLD without cirrhosis was observed when compared to other etiologies of chronic liver disease[1]. This is particularly concerning, since in a recent study 20% of NAFLD-related HCC occurred in the absence of cirrhosis[14]. The patient with non-cirrhotic NASH presenting HCC is older, male, and meets one or more criteria for metabolic syndrome[3,7].

The pathogenesis of HCC related to NAFLD is different, once metabolic syndrome and obesity manifest several exclusive mechanisms that favor the occurrence of tumors: increased release of free fatty acids, of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, and the reduction of activity of anti-inflammatory agents such as adiponectin[9]. The presence of these chemical mediators leads to apoptosis of hepatocytes, compensatory proliferation and, finally, carcinogenesis[2,7,13,25]. Accumulating evidence supports the importance of lipid metabolic reprogramming in various situations of hepatocarcinogenesis[26]. Given the increasing incidence of NAFLD and advances in curative options for hepatitis C viral infection, NAFLD is expected to become the leading cause of HCC in developed countries[2,3,27]. Absent washout and capsule appearance are associated with increasing hepatic steatosis in patients with non-cirrhotic, NAFLD-associated HCC[28]. Increased incidence of NASH-related cirrhosis is also influencing trends in liver transplantation: there has been a 4-fold increase in the number of liver transplants due to NASH compared to a 2-fold increase in those due to hepatitis C[2,5]. However, comparing to other etiologies of cirrhosis, it is not clear wether HCC-related NAFLD has similar outcomes[29,30]. In addition, NASH has already become the second leading cause of HCC-related liver transplantation in USA[2].

HCC represents the fifth most common neoplasm and the second largest cause of cancer mortality worldwide[2,31,32]. Despite its increasing incidence and the development of new therapies, overall 5-year survival is still low, no more than 30%[33,34]. NAFLD is considered to be the third cause for HCC in the USA[35]. Early detection of HCC provides greater treatment options, significantly improving the prognosis of patients[31]. NAFLD increased substantially over the past 20 years among resectable HCCs and it is now the leading cause of HCC occurance without or with minimal fibrosis[36]. In terms of clinicopathological findings, most studies agree that noncirrhotic NAFLD-related HCC patients were more likely to present with larger tumors[37-39]. Although there are guidelines for routine HCC surveillance that allow early diagnosis and improvement in curative outcomes, overall screening rates are below those considered ideal[31,32]. In addition, it has been found that patients with cirrhosis due to NASH are less likely to undergo adequate checks and monitoring of HCC compared to patients with other etiologies for chronic liver disease[1,5,31]. This may be due to the lack of HCC screening in noncirrhotic NAFLD patients[31]. It is widely reported that the deficiency in HCC surveillance among NAFLD patients, with only 13% of HCC discovered through surveillance, resulted in delayed detection in the majority of patients[40]. Several factors may contribute to this phenomenon: visceral adiposity, for example, is associated with a lower degree of ultrasonographic tumor identification, limiting its sensitivity for screening[1]. Other related variables are attributed to difficulties in access to adequate health care[31]. Patients with NAFLD-related HCC are older, have a shorter survival time, have more cardiovascular diseases and diabetes and are more likely to die from their HCC than other patients[41-43]. It has been demonstrated that curative treatment for HCC and serum albumin level > 3.7 g/dL suggest best prognostic profile for NAFLD-related HCC[44].

Evidence of hepatocarcinogenesis arising in the absence of advanced fibrosis is of concern, as recent guidelines recommending ultrasonographic abdominal screening and surveillance for HCC, every 6-12 months, only for patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B infection, failed to address this growing patient population[1,2,7]. In addition, those with NAFLD-related HCC have a worse prognosis, since they have a shorter survival time, a more advanced tumor at diagnosis and a lower probability of liver transplantation[31,45]. This reinforces the idea that a rewording of current HCC screening recommendations is needed so that these high-risk patients can be diagnosed via routine assessment[3,5,46]. It is also understood that, because of the high prevalence of this type of liver disease, the extension of screening to this whole group would greatly increase health spending, making it less viable[47]. Stratification by fibrosis score may offer some additional benefit to the subgroup of patients with non-cirrhotic NASH; however, reports of HCC in patients with NAFLD and no fibrosis have been described, such as the reported case. Further research to elucidate the association between the degree of fibrosis and the risk of HCC would provide a useful tool in the screening for HCC in these patients[1]. PNPLA3 gene polymorphism has been associated with an increased risk of HCC and may assist in assessing the patient’s risk and personalizing surveillance. However, it has not yet been validated for routine use because there is no well-documented cost-benefit ratio[4].

American Association for the Study of the Liver, European Association for the Study of the Liver and the Brazilian Society of Hepatology do not recommend routine HCC screening in non-cirrhotic NASH patients justifying that the large population of NAFL/NASH patients makes systematic surveillance impracticable[4,12,35].

Conclusion

With increasing cure rates for chronic liver disease related to HBV and HCV, NASH may become the leading cause of HCC and liver transplantation in the coming decades. Recent evidence shows that a significant proportion of patients with NAFL and NASH progresses to HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis or fibrosis. However, new effective monitoring and screening measures should be established to address these high-risk patients, thereby reducing the future impact of HCC in this population.

Declarations

Authors’ contributionsConception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation: Onzi G, Moretti F, Soldera J

Data acquisition, provided administrative, technical, and material support: Onzi G, Moretti F, Soldera J, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipNone.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2019.

REFERENCES

1. Stine JG, Wentworth BJ, Zimmet A, Rinella ME, Loomba R, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:696-703.

2. Cholankeril G, Patel R, Khurana S, Satapathy SK. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: current knowledge and implications for management. World J Hepatol 2017;9:533-43.

3. Chagas AL, Kikuchi LO, Oliveira CP, Vezozzo DC, Mello ES, et al. Does hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis exist in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients? Braz J Med Biol Res 2009;42:958-62.

4. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64:1388-402.

5. Oda K, Uto H, Mawatari S, Ido A. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of human studies. Clin J Gastroenterol 2015;8:1-9.

6. Chu H, Williams B, Schnabl B. Gut microbiota, fatty liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Res 2018;2:43-51.

7. Perumpail RB, Wong RJ, Ahmed A, Harrison SA. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of non-cirrhotic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: US experience. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:3142-8.

8. Yatsuji S, Hashimoto E, Tobari M, Taniai M, Tokushige K, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis compared with cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:248-54.

9. Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, et al. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:1972-8.

10. Mahady SE, Adams LA. Burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33:1-11.

11. Piñero F, Pages J, Marciano S, Fernández N, Silva J, et al. Fatty liver disease, an emerging etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Argentina. World J Hepatol 2018;10:41-50.

12. Cotrim HP, Parise ER, Figueiredo-Mendes C, Galizzi-Filho J, Porta G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease brazilian society of hepatology consensus. Arq Gastroenterol 2016;53:118-22.

13. Said A, Ghufran A. Epidemic of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Clin Oncol 2017;8:429-36.

14. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, Natarajan Y, Chayanupatkul M, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1828-37.

15. Ioannou GN, Green P, Lowy E, Mun EJ, Berry K. Differences in hepatocellular carcinoma risk, predictors and trends over time according to etiology of cirrhosis. PLoS One 2018;13:0204412.

16. Reig M, Gambato M, Man NK, Roberts JP, Victor D, et al. Should patients with NAFLD/NASH be surveyed for HCC? Transplantation 2019;103:39-44.

17. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73-84.

18. Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2013;9:13-27.

20. Wong SW, Ting YW, Chan WK. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma and its implications. JGH Open 2018;2:235-41.

21. Bulathsinhala BKS, Siriwardana RC, Gunetilleke MB, Niriella MA, Dassanayake A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma: results from prospective study, from a tertiary referral center in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J 2018;63:133-8.

22. Mak LY, Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, Torres HA, LoConte NK, et al. Global epidemiology, prevention, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;23:262-79.

23. Argyrou C, Moris D, Vernadakis S. Hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Is it going to be the “Plague” of the 21st century? A literature review focusing on pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. J BUON 2017;22:6-20.

24. Massoud O, Charlton M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2018;22:201-11.

25. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Muralidharan P, Raj JP. Update in global trends and aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2018;22:141-50.

26. Nakagawa H, Hayata Y, Kawamura S, Yamada T, Fujiwara N, et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2018; doi: 10.3390/cancers10110447.

27. Reeves HL, Zaki MY, Day CP. Hepatocellular carcinoma in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and NAFLD. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:1234-45.

28. Thompson SM, Garg I, Ehman EC, Sheedy SP, Bookwalter CA, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: effect of hepatic steatosis on major hepatocellular carcinoma features at MRI. Br J Radiol 2018;91:20180345.

29. Sadler EM, Mehta N, Bhat M, Ghanekar A, Greig PD, et al. Liver transplantation for NASH-related hepatocellular carcinoma versus non-NASH etiologies of hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation 2018;102:640-7.

30. Wong CR, Njei B, Nguyen MH, Nguyen A, Lim JK. Survival after treatment with curative intent for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with vs without non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:1061-9.

31. Tavakoli H, Robinson A, Liu B, Bhuket T, Younossi Z, et al. Cirrhosis patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are significantly less likely to receive surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:2174-81.

32. Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Dal Castel M, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, et al. Intraparenchymal hemorrhage due to brain metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2017;11:516-25.

33. Soldera J, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Furlan RG, Terres AZ. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Austin J Gastroenterol 2017;4:1088.

34. Soldera J, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Cavalcanti AG. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to hepatocellular carcinoma: understanding the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Protocol. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol 2016;9:67-71.

35. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;67:328-57.

36. Pais R, Fartoux L, Goumard C, Scatton O, Wendum D, et al. Temporal trends, clinical patterns and outcomes of NAFLD-related HCC in patients undergoing liver resection over a 20-year period. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:856-63.

37. Schütte K, Schulz C, Poranzke J, Antweiler K, Bornschein J, et al. Characterization and prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the non-cirrhotic liver. BMC Gastroenterol 2014;14:117.

38. Leung C, Yeoh SW, Patrick D, Ket S, Marion K, et al. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1189-96.

39. Bertot LC, Jeffrey GP, Wallace M, MacQuillan G, Garas G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related cirrhosis is commonly unrecognized and associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun 2017;1:53-60.

40. Edenvik P, Davidsdottir L, Oksanen A, Isaksson B, Hultcrantz R, et al. Application of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in a European setting. What can we learn from clinical practice? Liver Int 2015;35:1862-71.

41. Mohamad B, Shah V, Onyshchenko M, Elshamy M, Aucejo F, et al. Characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients without cirrhosis. Hepatol Int 2016;10:632-9.

42. Zarrinpar A, Faltermeier CM, Agopian VG, Naini BV, Harlander-Locke MP, et al. Metabolic factors affecting hepatocellular carcinoma in steatohepatitis. Liver Int 2018; doi: 10.1111/liv.14002.

43. Kwon OS, Kim JH, Kim JH. The development of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Korean J Gastroenterol 2017;69:348-52. (in Korean)

44. Kawaguchi T, Tokushige K, Hyogo H, Aikata H, Nakajima T, et al. A data mining-based prognostic algorithm for NAFLD-related hepatoma patients: a nationwide study by the Japan study group of NAFLD. Sci Rep 2018;8:10434.

45. Huang Y, Wallace MC, Adams LA, MacQuillan G, Garas G, et al. Rate of nonsurveillance and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma at diagnosis in chronic liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018;52:551-6.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Onzi G, Moretti F, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Soldera J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis. Hepatoma Res 2019;5:7. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2018.114

AMA Style

Onzi G, Moretti F, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Soldera J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis. Hepatoma Research. 2019; 5: 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2018.114

Chicago/Turabian Style

Onzi, Georgia, Fernanda Moretti, Silvana Sartori Balbinot, Raul Angelo Balbinot, Jonathan Soldera. 2019. "Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis" Hepatoma Research. 5: 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2018.114

ACS Style

Onzi, G.; Moretti F.; Balbinot SS.; Balbinot RA.; Soldera J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis. Hepatoma. Res. 2019, 5, 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2018.114

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 16 clicks

Cite This Article 16 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.